|

DISPATCHES

|

||||

|

"AMBUSH" I was in the first wave of journalists to arrive in Jalalabad on November 15th, just a few days after the Taliban retreated from the region. We came in a convoy of fifteen buses from Peshawar, Pakistan on the first day that the Torkham border crossing was opened.

Harry was really not into this story. He had spent the last two years covering Indonesia and just wanted to get it over and done with so he could go home and spend time with his girlfriend. As the buses headed for the Torkham crossing, Harry had second thoughts. He said he was pretty sure he would get off at Torkham because things didn't feel right. At Torkham he and I got off the bus to film and photograph, and check out the situation. Harry got back on the bus with me and decided to continue on. I will never forget his irreversible decision. Many of the 200 strong press corps that made it to Jalalabad waited several days before making the decision to travel to Kabul. There was a prevailing false sense of security that developed amongst the media corps since Nangarhar Province, which includes Jalalabad, seemed under control and absent of conflict. After three days, so many people were driving back and forth between Kabul and Jalalabad without any hint of danger that it seemed safe to go. On the morning of November 15th, we arrived at the home of Abdul Haq in Peshawar, Pakistan, whose family was forming a motorcade to take journalists into Jalalabad. Our hosts, who were involved in cobbling together a Post-Taliban, coalition Pashtun government, were continually trying to impress us with the security there. This, I believe, contributed to our false sense of security. I huddled with Harry and several people from CBS News to discuss the security issues and weigh out the decision to go or not. We decided to go en masse as our hosts were promising things would be safe in their hands. At least, we were willing to take that chance. Many people headed out from Jalalabad to Kabul the morning of the 19th since the waters of the route had already been sufficiently tested. There wasn't a motorcade to speak of, just groups of cars leaving at several different points in the morning. Our group that morning, myself, Willis Witter, Deputy Foreign Editor of the Washington Times, and Laura Winter, a freelance writer based in Hong Kong, were not in a terrible rush. We simply wanted to get to Kabul before nightfall. I had to ask the waiter in our hotel five times to bring my coffee, which delayed us somewhat. We went to several gas stations before we found gas. This delayed us more and we wound up on the road thirty to forty five minutes behind the fateful group. We were on that road heading into the same ambush, just further behind. I will never forget the panic as the first car to flee the ambush came upon us in the opposite direction. Khaled Kazziha, a videographer for APTN, was waving his arms frantically from his car window. "Stop! Turn around! There's been an ambush! Five journalists were just killed up the road! Turn around!" In his car was one of the drivers that escaped, and the luggage of two of the victims. We turned around with him and began to warn all others coming up the road, regardless whether they were fellow journalists or local Afghanis.

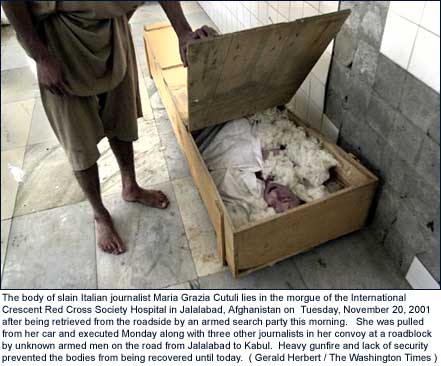

Maria Grazia Cutuli, an Italian journalist who was one of those killed, I met the night before. She was quiet and polite. A CBS employee who was acquainted with her flattered her, "What a beautiful name! Maria Grazia! Maria Grazia!" I asked her about her plans for tomorrow and told her I would see her in Kabul, as I was going as well. I didn't see her again until her body was retrieved from the roadside and brought to the morgue two days later. Her image in the morgue was like a mirror, revealing a fate that could have so easily been mine. The sight was sobering and painful. Her murder was of chance and tragic timing. I thought of her loved ones, and of mine. To the Taliban and al Qaeda, the beautiful name of Maria Gratzia and the Jesus face of Harry Burton were never a consideration at the time of their executions. All four of those journalists were innocent victims, just trying to cover the story. They had homes and loved ones to go home to in lands far away, where killing of the innocent is incomprehensible. Their murders were the textbook definition of terrorism, no different than those killed in the September 11 attacks. Their deaths were predetermined from the moment they were yanked from their cars. There were no negotiations, and how sweet or nice they were had no bearing on this outcome. Their pleas fell on the deaf ears of their killers. The day after the bodies were retrieved most of the news organizations retreated to Peshawar in a long, slow, heavily armed convoy with protection provided by Haji Qadir, the new Governor of Nangahar. I, like many of the others, have covered unrest many times before. I believe most of us wished to go home. Once back in Peshawar, one thought kept crossing my mind. What if I return to Afghanistan, and get killed there? How painful would that final moment be, knowing that I could have cut my losses and gone home, but instead walked right back into that peril, and lost my second chance on life?

Faced with life and death up close, through the mirror of my deceased colleagues, I'm broadsided with the sadness of their loss and reminded of my own frailty. Anyone who was out on that road that day can do nothing but second-guess their own judgment from that point on in Afghanistan. And in a land where the rules are not clear, and danger could be lurking behind any ridgeline or bend in the road, that is no way to work. I have always relied on my good judgment to navigate the dark roads of civil unrest. After all, I waited for four days worth of evidence that the road could be safely navigated. Reflecting back upon that fateful day, nothing seemed out of the ordinary and there was no indication that before noon I would be fleeing back to the safety of Jalalabad, Afghanistan while four of my colleagues lay dead along the roadside. The reality still hangs over my head that it was just a matter of timing that they met death, and that I was allowed to continue on. I greet all my friends and colleagues on my return home with my life, a privilege I will never take for granted. When you feel you are exercising reasonable judgment and your judgment has proven itself wrong, you have lost your road map. Unfortunately Harry Burton and three others lost it all. Gerald Herbert is a staff photographer for the Washington Times since 1999. He has covered conflicts in the Middle East and Haiti many times. Returning from Pakistan to his home in Alexandria Virginia, he says, "was like the best birthday I ever had." |

|

|

Write a Letter

to the Editor |

Harry

Burton, a cameraman from Reuters TV rode with me. I liked Harry so

much. He was one of the kindest and most gentle people I have ever

met. His long hair and beard, as well as his demeanor, reminded me

of Jesus.

Harry

Burton, a cameraman from Reuters TV rode with me. I liked Harry so

much. He was one of the kindest and most gentle people I have ever

met. His long hair and beard, as well as his demeanor, reminded me

of Jesus. Over

the next several hours the tragedy played itself out slowly as the

identities of those killed became clear. The names caused shock in

my heart and pits in the stomach.

Over

the next several hours the tragedy played itself out slowly as the

identities of those killed became clear. The names caused shock in

my heart and pits in the stomach.