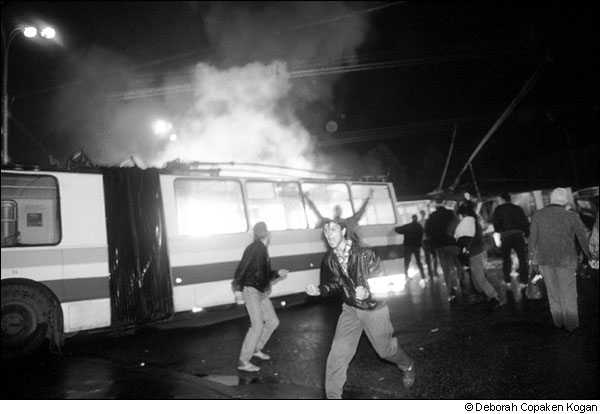

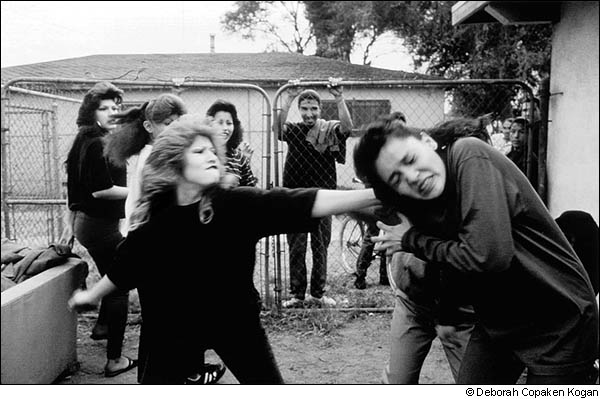

What do you say to a woman you have never met, yet feel you know intimately? How do you relate to someone when you know some of his or her most personal thoughts and feelings, yet they have absolutely no idea who you are? These were the thoughts going through my mind as I prepared to interview Deborah Copaken Kogan. Deborah's autobiography about her years as a female photojournalist covering conflict zones around the world during the late 80s and early 90s was recommended reading in the Advanced Photojournalism class at the University of Texas at Austin. I was fascinated by the adventures detailed in her book Shutterbabe, as well as her ability to write about her successes and devastating losses with such honesty and humor. I wanted to talk to her, to understand the motivation behind her decisions to take such incredible risks in her personal and professional lives, and why she chose to write about them. Deborah graduated from Harvard in 1988, and armed with only her cameras and her youth, she moved to Paris, seeking out conflicts to photograph. What she found was equal parts men and guns, a fast-paced Darwinian world where survival of the fittest meant capturing death on film. Throughout the gritty tale of her four years as a photojournalist, the lines between the bloody international conflicts she was documenting and her own emotionally harrowing relationships blur as she leaps from one corner of the earth to another with breathtaking speed. As a young photojournalist, there was one question I was burning to ask Deborah: What difference did any of this noble globetrotting make? It is a question that she reflects on in her book, one that haunted her during her time overseas. To awaken each day knowing that in order to survive, someone must die, and to hope that the death is a particularly violent and newsworthy one? Is this the life of a vulture, sifting through the bodies of the latest tragic conflict, using suffering and pain for your own personal glory? Does it all boil down to changing the course of world politics, or is the ultimate result only a few snapshots that fail to make any sort of cohesive statement, but allow for substantial bragging rights?

I reached Deborah in her New York City apartment that she shares with her husband Paul and two children Jacob and Sasha. She was as frank and thoughtful in answering my question as she was in describing the distressing events in her book. "I thought about that every single day," she said. "It's always in the back of your mind. Am I a vulture? Am I stealing? Am I giving or am I taking?" While the answer to this question is not always clear, there is one instance in Deborah's mind that makes all the difference. "It has been the greatest irony of my career that the one time I truly made an impact, it wasn't even with my photographs," Deborah said. In the months following the fall of Romanian dictator Nicolae Ceausescu in 1989, Deborah and her companions discovered an orphanage in the Romanian countryside. The orphans living there were referred to as “unrecoverables,” and the deplorable conditions she witnessed left Deborah physically ill. She managed to photograph the horrific scene, and sent the photos off to her agency in Paris. Several days later, her editor informed her that the images were too grotesque to be sold. Later that day, photographer James Nachtwey arrived in Bucharest from a previous assignment. Deborah gave him not only a precious brick of Tri X film, but also handed over the address of her exclusive and begged Nachtwey to go to the orphanage. An internationally renowned photographer, Nachtwey held the eyes of the world in the palm of his hand, along with the clout to get such a story published. He traveled to the orphanage as he had promised, and the result was one of the most powerful visual statements of the consequences of the downfall of the Soviet bloc. The photos ran over 12 pages in The New York Times Magazine, and resulted in international aid for the orphans. Deborah was eventually able to sell her photos of the orphanage as well, and has no regrets about giving her biggest story away. “That decision makes me feel great,” said Deborah. “It was the right thing to do.” Although Deborah demonstrates the greatest admiration for Nachtwey in her writing, her view of his life dedicated solely to photojournalism has changed since she left the profession. War Photographer, a documentary by Swiss producer Christian Frei, chronicles two years in Nachtwey’s life as a photojournalist, following him into Indonesia, Kosovo, and the West Bank. In Shutterbabe, Deborah describes Nachtwey’s reputation as a focused professional who remains perfectly groomed as he dashes into battle, known among her colleagues as “the god of photojournalism.” She saw him as a man on a mission, whose reason for living was recording human suffering around the world in an effort to alleviate it. Deborah’s youthful, idealistic view of Nachtwey’s dedication to his work has dulled, and in its place is the inquisitive voice of a woman who questions this myth of a man. “Does he live his life with conviction, or is it denial?” Deborah asked. “What are the negative aspects of how he is living?” Now that she has left the life of the war photographer behind, Deborah sees Nachtwey’s lack of relationships as a weakness. “People like Jim who are obsessed with their work, and have no human relationships, are unanalyzed. There is great work, but at what cost? What do you value in life? Is it friendship and love? He made the documentary because he has to justify not having relationships.” Nachtwey has been knocked off the pedestal Deborah held him on for years. It is just one part of her journey, she says. “To be human is to question what you’re doing, all the time. Convincing yourself is part of the game, that’s what being human is.” In the years since Shutterbabe ended, Deborah has continued to evolve from the bored teenager she was growing up in Potomac, Maryland. Woven into her memoir, alongside tales of her various conquests on the battlefield and in the bedroom, is a reflection on her childhood. In these touching moments, Deborah reveals her acute awareness that she was not ready to become a mother herself. She and her husband, Paul Kogan, met in Paris in 1990, lived together in Moscow during the 1991 revolt that put Yeltsin in control of Russia, and were married in 1993. Deborah explains the sudden change in her outlook on relationships by simply saying, "You can’t help falling in love, you just do." At 36, she has taken a non-traditional path to play what some would consider a traditional role. "I was so anti-normal life," Deborah said, when I asked her if this were how she imagined her life would be when she was older. "I was very sheltered when I was growing up in the suburbs. We are only as knowledgeable as our upbringing, and I did not want to bring children into the world to experience the same childhood I experienced." Deborah’s path to parenthood was unarguably the one less traveled by. In Shutterbabe, she often reflected on her position as a female in a man’s world, both in the realm of photojournalism and beyond. “Women have difficult decisions to make. If you’re a female at the top of your profession, you travel all the time, and you want to have kids, you have to decide how to do it. Men don’t have to think that way. Do I quit during my pregnancy? No man ever had to make that choice.” Deborah’s doubts about parenting faded once she was married, and she and Paul decided to start a family. “We had this insane desire to have a child,” said Deborah. “It was all we thought about.” As for the insinuation that she sold out to become a mom, Deborah doesn't see her life that way. “The battles in a war zone are similar to the ones still being fought on the feminist front. There is a cultural bias that says that a woman who doesn’t have a 9 to 5 job is a stay at home mom. What male author would ever be called a stay at home dad? I worked every day for 2 years writing the book. I had a contract, I worked away from the house, and I was making twice my salary at Dateline.” Juggling work and family hasn't been easy, but has improved since she stopped working in television. After working for Dateline NBC for six years, Deborah quit her job to work independently and spend more time with her kids. "Corporate America is anti-family," she said. "I'll never go back to that. Being a writer is the perfect job. I have control, I can be a mom, make money, and still see that the homework is done.” Spending time with her husband and children remains her top priority, but Deborah has not stopped working since she got married and had kids. Among her many projects is a movie based on Shutterbabe with DreamWorks, which is being written, directed, and produced by Darren Star. She is also working on a photography project, and continues to write articles and take photographs for a variety of magazines, including O Magazine and Rosie, and is writing a novel. I wanted to know what the novel is about, and in her typically candid manner, Deborah explained that she did not want to talk about it, fearing that she would lose interest in finishing it. "I have found that when you’re writing a novel, the more you talk about it, and the more you tell the story over and over, the less interested you are in actually writing it down. It loses its magic." As for the plot, she would only laugh and say, “It's about people." The photography project she is currently working on is a departure from her years of training and practice as a news photographer. “It’s a diary form photo project. The only rule is that I can’t seek out pictures,” said Deborah. “I can’t go looking for them, they have to come to me. I’ll see something, like my husband paying the bills with his brow furrowed, and I’ll take a photo.” The March 2002 issue of O Magazine featured an article written and photographed by Deborah about her trip to Peshawar, Pakistan with Jacob. Mother and son traveled to Pakistan together to give the school supplies, money and toys collected by Jacob's school to the Afghan refugees living in Pakistan. Although she was criticized for taking her six-year-old son so close to the heart of the conflict in the Middle East, Deborah sees her decision as a necessary one. "I have learned that no matter what you do, someone is going to hate it,” she said. "As Americans, we close our eyes to global issues and it is to our detriment." Traveling with her young son may not be a life that her former Shutterbabe persona would envy, but Deborah is unapologetic about her professional choices. “I have gone from having a need for the absolute, extreme experience to appreciating the small moments, which I couldn’t do until I became a parent. Motherhood is the beginning, not the end. It’s more fulfilling.” Giving up the photojournalist lifestyle was not difficult for Deborah. “If you’ve seen one war, you’ve seen them all. I didn’t want to witness the atrocities anymore. Someone has to be there to record them, but I didn’t want to be that person. It is disturbing and frightening. Also, it was time to start a family.” Shutterbabe may be dead, but Deborah will always see the world through her shutter, still carving out the little rectangles she has been fascinated with since discovering photography. “Photography still feeds me. It opened up another dimension to me. If you have it in your blood, if you have the drive, it will always be there.”

Will Deborah's legacy be that she was a great photographer, or a great mother? "I don't think about how I want to be remembered. That’s a more masculine attitude. Men may care about how they are seen in a historical light, but to me outside approval is less important than feeling that I am a good human, and a good spouse. All I want is to feel that my kids are loved and that I have a job I love," Deborah said. "Going back out and seeing the same old photographers, the same old faces, screaming into their cell phones-it's not my life anymore. Would I want that life now, at age 36? No way." While talking to Deborah, I realized that what drives her is an intense desire to understand what it is to be human. Like a carefully printed photograph, there is very little black and white, but many subtle shades of gray. © Anna Moorhead |

|

|

Write a Letter

to the Editor |