However, this beautifully edited and produced book

(designed by the British genius Mark Holborn and printed by Tipocolor

in Florence, Italy) is only about Vietnam, the war which - as David

Halberstam explains in his introduction - was "the great assignment

Larry Burrows always wanted" and the war which was very essentially

his own. Had he lived, I would have expected to see him at the reunion of former Vietnam correspondents in Ho Chi Minh City (Saigon) in April 2000, commemorating the 25th anniversary of the end of the war. He was there as an 'absent friend' who had enriched the professional lives of almost everybody who could be in HCMC for the anniversary. If there would have been a vote for the most respected and loved newsperson in Vietnam, Larry would have almost certainly come out tops, closely followed by Henri Huet of The Associated Press, who died with him in the helicopter crash on February 10, 1971, and Dang Van Phuoc, the greatest of Vietnamese combat photographers , himself admired by Larry for many years. Phuoc now lives near Los Angeles.

Had he lived, Larry would have seen that much of his

work is displayed prominently on the walls of the "War Remnants

Museum" in Saigon. I could see him in my mind, smiling that typical

private and polite Larry-Burrows-smile, watching crowds of young Vietnamese

studying his photographs close-up, commenting, "Well, nice of these

chaps to look at my photographs. I hope they grow old to have a better

life." The stark reality that Larry Burrows had to die in

a flaming helicopter struck me hard, when strips of long-corroded film,

lens parts and a Leica camera, damaged with the force of a hammer blow,

were scraped from a jungle hillside in Laos in March 1998. My AP colleague

Richard Pyle and I watched Laotian workers and an American recovery

team searching the crash site, twenty-seven years later. Exploring the

history of the Leica later by means of its serial number we were directed

back to 1960, London, LIFE Magazine. It was most likely a Leica body

purchased to replace equipment Larry had lost while covering the turmoil

in the Congo in July 1960, following he Congo's Independence Day. Larry and I crossed paths first in Saigon, summer 1962,

both sent to Vietnam by our respective photo editors in New York "to

find out what's going on out there". Larry became a friend and regular visitor to the AP office and we exchanged without hesitation story ideas, tips about upcoming military operations, contacts. I knew that in these days Larry would make his daily rounds to learn from everybody what was going on: Visiting other agencies, to chat with Dave Halberstam and Neil Sheehan (who worked together at the UPI office), the TV correspondents' suites at the Caravelle, the Givral Café and the English journalists residing at the old-worldly Hotel Royal. Larry was absolutely discreet, so discreet that nobody really knew what he was up to until another blockbuster appeared in LIFE, sending us all scrambling to produce "matchers". It was not possible to work side by side with Larry

- and I don't recall having been near him on one of the major military

operations. Usually Larry disappeared as mysteriously from Saigon as

he returned, leaving everybody guessing what he was up to. Even the

more chatty "chaps" from Time Magazine and the occasional

visiting LIFE correspondent or photographer could not be helpful to

trace Larry as they didn't know themselves. Larry Burrows' first big Vietnam story (with 14 pages,

a fold-out cover and inside foldout pictures, much in glorious color

), "The Vicious Fighting in Vietnam" from January 1963 established

him as the master of the Vietnam reportage. In one big sweep the important

aspects and the confusion of the war in Vietnam was masterly told. The

world of U.S. advisors and local tipsters was small in these days and

while we knew that Larry was in the Delta with the Vietnamese Rangers,

or the Air Force in Bien Hoa, it all did not make much sense to us since

he obviously did not rush to the airport to ship film after his returns

to Saigon. For many years I asked photographers to read Graham

Green's "Quiet American" and Bernhard Fall's "Street

Without Joy" on the plane ride to Saigon. Then, in the office,

I showed them a 1954 photo book "La Guerre Morte" with superb

photography from the French Indochina War - and Larry Burrow's "The

Vicious Fighting". Just to get an idea what levels we need to achieve

to make a point at all. With some envy we agency photographers helicoptered in and out of any action (or non-action) as quickly and as often as possible, to produce the daily Vietnam war radiophoto quota for daily newspapers.

While Larry was possessive of his stories he also knew

what was good for LIFE Magazine: When Henri Huet was once trapped with

an embattled U.S. First Cavalry unit in the Central Highlands Larry

heard about it and waited in the AP office for Henri's return. "Knowing

Henri, he will come back with something useful." What also made me feel envy were the many other stories

Larry Burrows was assigned to between his Vietnam visits. Even Vietnam

could become stale. But AP, always keen for the hard news from the war,

were rarely susceptible to feature suggestions. I saw Larry Burrows last in Calcutta, late January

1971. I had been sent there to illustrate AP stories on the poverty

in Calcutta and Mother Theresa`. Larry was working on an (unfinished)

project about Calcutta. The days we met he spent time in the museums

to copy old paintings from the history of the city. He told me how long

it took him to learn to photograph a painting, with a proper reproduction

of the colors, without any glares and evenly lit. He told me how he

once photographed the art of Europe for a LIFE series with Dimitri Kessel.

Vietnam was far away, but as always in the back of our minds - until

we both got telexes to make it to Saigon as quickly as possible. An

invasion of Laos was imminent. Larry smiled: he had a visa in his passport.

I had to stop over in Singapore to get my visa. Larry stopped over at

the AP office and heard that Henri Huet was up front and then headed

north himself. I made it to the AP's Saigon office a few days later

on February 10, the day Larry and Henri and the others died. © Horst Faas

|

|

Write a Letter

to the Editor |

W

W

Early

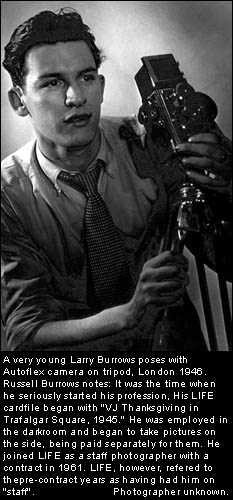

photos show Larry fingering a Speed Graphic camera, then a Rolleiflex.

Then of course, Leicas and Nikons. I have similar photos in my scrapbooks.

Early

photos show Larry fingering a Speed Graphic camera, then a Rolleiflex.

Then of course, Leicas and Nikons. I have similar photos in my scrapbooks.

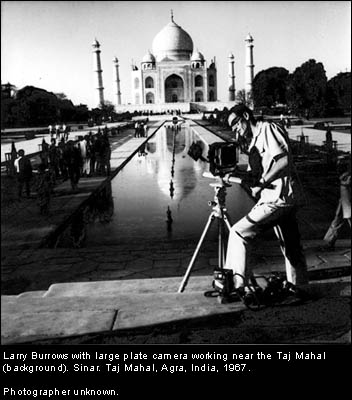

In 1962

it was the war between India and China in the beautiful and dramatic

landscape of the Himalayas.

In 1962

it was the war between India and China in the beautiful and dramatic

landscape of the Himalayas.