|

It’s as Close to Marilyn Monroe

as I’m Ever Going to Get

April 2003

by CHERYL DIAZ MEYER |

|

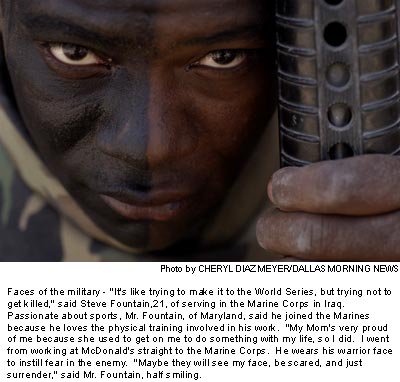

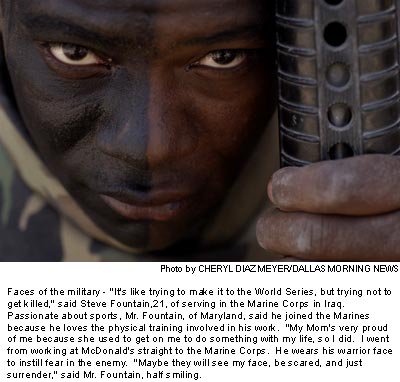

Forty-five seconds

of whistles, cheers and thunderous clapping roar in my ears. An eternity

of applause. It’s as close to Marilyn Monroe as I’m ever

going to get. I can’t help but smile and try to ignore the deep

embarrassment that is welling inside me for this attention I do not

deserve and did not earn. In truth, they are cheering not for me, but

for their women folk, their wives, mothers, sisters, daughters and I

represent all of those people to them. I am the woman they have missed

for weeks and months, the woman for whom they long. I am the woman for

whom they will survive this war.

Before

me is a crowd of some 2000 U.S. Marines. Sweat and dust cover their

tanned faces and have become woven into the threads of their khaki uniforms.

They stand in the cool evening of a Kuwaiti desert in the barracks called

Camp Coyote, home of the Second Tank Battalion, where I have been embedded

with my writer, Jim Landers. Lt. Col. Oehl has announced a talent show

to keep spirits up and the Marines take this opportunity to strut their

stuff: the good, the bad, and indeed, the ugly. It’s a numbing

show, like something out of a movie. It’s not quite real, and

yet the clapping reverberates in my heart and reminds me that the dust

and grit is very real. Each person there knows that with every hearty

laugh and every good-humored joke that we will go to war, and it is

highly likely that some of us will not return. Before

me is a crowd of some 2000 U.S. Marines. Sweat and dust cover their

tanned faces and have become woven into the threads of their khaki uniforms.

They stand in the cool evening of a Kuwaiti desert in the barracks called

Camp Coyote, home of the Second Tank Battalion, where I have been embedded

with my writer, Jim Landers. Lt. Col. Oehl has announced a talent show

to keep spirits up and the Marines take this opportunity to strut their

stuff: the good, the bad, and indeed, the ugly. It’s a numbing

show, like something out of a movie. It’s not quite real, and

yet the clapping reverberates in my heart and reminds me that the dust

and grit is very real. Each person there knows that with every hearty

laugh and every good-humored joke that we will go to war, and it is

highly likely that some of us will not return.

I have taken a liking to our colonel. He’s a

genuine, no-nonsense, low-key man who passes on a quiet confidence to

his men. I have been living with 6,000 men in a camp where only a handful

of women have stepped. One other female journalist was embedded with

another unit about a half mile away, and there were some female engineers

who were temporarily in the area, but I was told they had left.

During my short time in the camp, the men have treated

me with respect, generosity and kindness. I have grown fond of these

men from all over the United States, who serve their country and endure

tremendous obstacles to see that our government’s wishes are fulfilled.

I have been adopted. I have inherited a thousand big brothers.

On

the morning that President Bush was scheduled to make his speech declaring

war, we were awakened with a start at 3 am and told to pack: we were

leaving in three hours for war. I made quick decisions in the dark about

what to bring and what to leave in my secondary bag, the one that would

follow in the field train some eight hours behind. We were supposed

to have two days’ notice to prepare, to let loved ones know that

they would not hear from us for awhile...until we entered Iraq. Instead

we woke up to the shock of war: tanks rumbling over the earth beneath

us, and no way for us to call. The goal was to surprise the Iraqis with

our stealth. We proceeded to the DA, short for dispersal area. The Lieutenant

Colonel decided not to move us temporarily to a TAA, a tactical assembly

area, whereupon the troops then move to the DA, and then on to cross

the LA, the line of departure or, in other words, the border. On

the morning that President Bush was scheduled to make his speech declaring

war, we were awakened with a start at 3 am and told to pack: we were

leaving in three hours for war. I made quick decisions in the dark about

what to bring and what to leave in my secondary bag, the one that would

follow in the field train some eight hours behind. We were supposed

to have two days’ notice to prepare, to let loved ones know that

they would not hear from us for awhile...until we entered Iraq. Instead

we woke up to the shock of war: tanks rumbling over the earth beneath

us, and no way for us to call. The goal was to surprise the Iraqis with

our stealth. We proceeded to the DA, short for dispersal area. The Lieutenant

Colonel decided not to move us temporarily to a TAA, a tactical assembly

area, whereupon the troops then move to the DA, and then on to cross

the LA, the line of departure or, in other words, the border.

We loaded into our AAV, an amphibious assault vehicle

that was to take us into Saddam Hussein’s never-never land. We

traveled for hours, bouncing around in the back of our metal box. We

set up camp at the DA, only to be told hours later to tear down our

tents immediately. We would be moving closer yet to the border.

We intended to stay a couple of days until news trickled

in that the GOSPs (gas, oil separation plants) were being set on fire,

in the south. Several times we were thrown into high alert when artillery

was fired on another group of Marines several miles away, and we suited

up in our full NBC suits, nuclear biological chemical suits, sweating

our brains out in 100-degree desert temperatures. Once again, we hurriedly

tore down tents and threw our belongings together to cross the DA ASAP,

so we could save the GOSPs. It seemed that this whole military embed

thing was really a tactical maneuver to give all of us journalists the

workout of our lives, and a heart attack to boot.

A couple of ABC television reporters joined us and

they, along with my reporter and a CBS radio fellow stomped around the

inside of our AAV trying to get a good angle on the few mortars and

artillery that hit several miles away. All of the action was aimed at

us and we were under direct attack, according to their breathless reports.

I could not reach the hatch to see much and with my bulletproof vest

and Kevlar helmet, I could barely hold myself vertical. I huddled in

the corner with my two cameras hugged to my body, dodging boots, not

bullets, that came a little too close, and feet that I feared might

have snapped me in two as bodies came landing alongside me just missing

my vitals.

It’s

been a few days since that momentous night: March 20,2003. We were some

of the first to enter Iraq, but have seen little action as we progress

north. It is not good strategy for a tank battalion to enter smaller

towns where it cannot maneuver the streets and damage sewage lines,

so we work our way west and let the infantry take the towns and cities

of Al Basrah and An Nasiriyah. I am frustrated to not be exposed to

any action and I continue to make pictures of Marines sleeping, convoying,

surviving dust storms and getting ready for battles that never materialize.

I came to cover a war, but it has become so dangerous that my bosses

won’t permit me to cover anything independently. I must continue

traveling with the military. It’s

been a few days since that momentous night: March 20,2003. We were some

of the first to enter Iraq, but have seen little action as we progress

north. It is not good strategy for a tank battalion to enter smaller

towns where it cannot maneuver the streets and damage sewage lines,

so we work our way west and let the infantry take the towns and cities

of Al Basrah and An Nasiriyah. I am frustrated to not be exposed to

any action and I continue to make pictures of Marines sleeping, convoying,

surviving dust storms and getting ready for battles that never materialize.

I came to cover a war, but it has become so dangerous that my bosses

won’t permit me to cover anything independently. I must continue

traveling with the military.

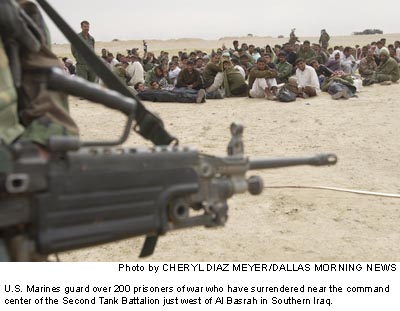

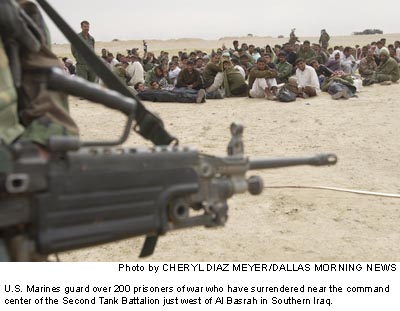

Stories trickle in of ambushes, deaths and hostages

being taken to Baghdad. We have heard of reporters being killed by friendly

fire and of Iraqis posing as journalists. The Marines of the Second

Tank Battalion are weary of hours of dusty roads but stay on guard for

possible attacks by smiling, white banner-toting Iraqis.

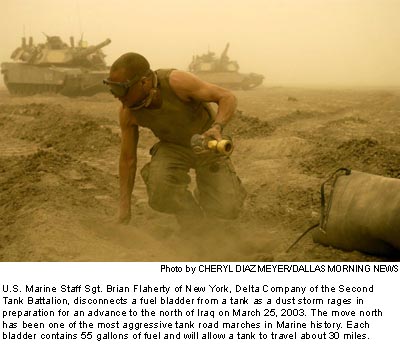

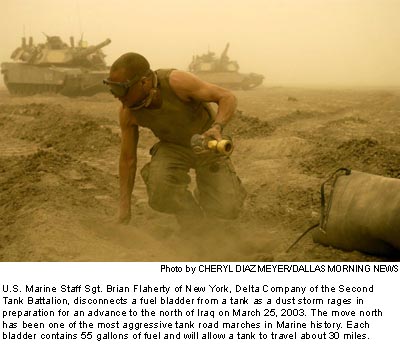

At

this point we are headed north to take on one of the last Iraqi army

divisions in the north. The Marines are not set up to travel more than

60 miles away from port, yet we are some 300 miles away from the nearest

one and our supply trains can hardly keep up with us. We wait for days

for the fuel trucks to arrive, only to have enough fuel to travel 30

miles. At

this point we are headed north to take on one of the last Iraqi army

divisions in the north. The Marines are not set up to travel more than

60 miles away from port, yet we are some 300 miles away from the nearest

one and our supply trains can hardly keep up with us. We wait for days

for the fuel trucks to arrive, only to have enough fuel to travel 30

miles.

Last night we survived a nasty dust storm in our military

hummer. The wind whipped around at 60 Mph tossing our vehicle to and

fro. We gasped and coughed for breath, covering our faces with scarves

and T-shirts to filter the air. We had one casualty, a pigeon that the

chem/bio guys have been keeping to help detect an attack. At four PM,

it was completely dark and we could not see five feet ahead of us. Being

outside was like having one’s face sandblasted. A large piece

of metal fell on one of our Marines as he worked furiously to patch

together a tank to make another death-defying trek north. We thought

he might be paralyzed. Others dared the wind and dust to get help. We

feared that people would get lost as they tried to walk from one vehicle

to another. Just when we thought things couldn’t get worse, news

filtered in that three unrecognizable tanks were cruising by not far

from our encampment. Fearing that their thermal tank sights might detect

us through the dust and fire a few rounds at us, we donned our body

armor and helmets and waited to see what they would do. Although they

may be hugely underpowered compared to our M1 Abrams tanks, they could

do some damage if they hit a vehicle like our little hummer.

I

haven’t had a wash in six days and am as dirty as I can recall

ever being in my entire life. We are living in some of the dirtiest

conditions imaginable with dust; dust and more dust everywhere and still

no bath in sight. We live in extreme heat during the day with wet, chilled

temperatures at night. All my companions are sick with respiratory infections.

I, too, have developed a cold and appease myself from the complete misery

of the situation with little bits of chocolate I bought before leaving

Kuwait. There are no more tents, no more sleeping bags, just body armor

to keep one’s neck propped up at night. There is no comfortable

position. We must be ready to leave at a moment’s notice. I

haven’t had a wash in six days and am as dirty as I can recall

ever being in my entire life. We are living in some of the dirtiest

conditions imaginable with dust; dust and more dust everywhere and still

no bath in sight. We live in extreme heat during the day with wet, chilled

temperatures at night. All my companions are sick with respiratory infections.

I, too, have developed a cold and appease myself from the complete misery

of the situation with little bits of chocolate I bought before leaving

Kuwait. There are no more tents, no more sleeping bags, just body armor

to keep one’s neck propped up at night. There is no comfortable

position. We must be ready to leave at a moment’s notice.

A

couple of nights ago, we arrived at our new camp after traveling some

ungodly amount of miles with the tanks. Exhausted and cranky, I prepared

to fight with my satellite phone to try and transmit some images from

the field. Five minutes later, a 50-caliber machine gun blasted several

rounds just yards from me. A young infantryman grabbed me and threw

me to the ground, covering me with his body. He dragged me up and then

pushed me toward the back of a hummer. Eyes wide and fearful, I breathed

hard and painfully as we waited for another round to fire. It was so

close that our chances for escape would have been low if indeed we were

under attack. Moments later, screams of A positive! filtered through

the dark night and we realized that someone had been hurt. It was a

26-year-old Lance Corporal from New York, and he was dead immediately.

A fellow tanker had accidentally pressed the safety switch on his gun

while getting out of his tank and it set the machine off killing the

lance corporal in the neighboring tank. Although I am permitted by the

rules of our embedment to photograph such situations, the Marines in

charge were too freaked and would not permit me to make photographs.

I can understand their sentiments. But I explained to them that I am

not traveling with them to do a public relations campaign. I am there

to document their experiences, in all that entails. War sometimes entails

death. It’s difficult to imagine what our military personnel go

through to conduct a war. It is truly the most wretched of circumstances.

Even before I met up with the Marines at Camp Coyote, some hadn’t

had a shower in weeks. Many suffer from trenchfoot and other unsavory

conditions. Yet they continue to work as hard as they can to do their

jobs right and with pride. It struck me immediately when I entered the

sphere of the Americans in Kuwait. Whereas in my five-star hotel in

Kuwait I never knew if a man would walk ahead of me or behind me through

a door, I always knew among the Marines that I would be given the right

of first entry. It feels good to be among our men. Chivalry is still

alive among them. A

couple of nights ago, we arrived at our new camp after traveling some

ungodly amount of miles with the tanks. Exhausted and cranky, I prepared

to fight with my satellite phone to try and transmit some images from

the field. Five minutes later, a 50-caliber machine gun blasted several

rounds just yards from me. A young infantryman grabbed me and threw

me to the ground, covering me with his body. He dragged me up and then

pushed me toward the back of a hummer. Eyes wide and fearful, I breathed

hard and painfully as we waited for another round to fire. It was so

close that our chances for escape would have been low if indeed we were

under attack. Moments later, screams of A positive! filtered through

the dark night and we realized that someone had been hurt. It was a

26-year-old Lance Corporal from New York, and he was dead immediately.

A fellow tanker had accidentally pressed the safety switch on his gun

while getting out of his tank and it set the machine off killing the

lance corporal in the neighboring tank. Although I am permitted by the

rules of our embedment to photograph such situations, the Marines in

charge were too freaked and would not permit me to make photographs.

I can understand their sentiments. But I explained to them that I am

not traveling with them to do a public relations campaign. I am there

to document their experiences, in all that entails. War sometimes entails

death. It’s difficult to imagine what our military personnel go

through to conduct a war. It is truly the most wretched of circumstances.

Even before I met up with the Marines at Camp Coyote, some hadn’t

had a shower in weeks. Many suffer from trenchfoot and other unsavory

conditions. Yet they continue to work as hard as they can to do their

jobs right and with pride. It struck me immediately when I entered the

sphere of the Americans in Kuwait. Whereas in my five-star hotel in

Kuwait I never knew if a man would walk ahead of me or behind me through

a door, I always knew among the Marines that I would be given the right

of first entry. It feels good to be among our men. Chivalry is still

alive among them.

© CHERYL DIAZ MEYER

Cheryl is a staff photographer

for The Dallas Morning News

|

Before

me is a crowd of some 2000 U.S. Marines. Sweat and dust cover their

tanned faces and have become woven into the threads of their khaki uniforms.

They stand in the cool evening of a Kuwaiti desert in the barracks called

Camp Coyote, home of the Second Tank Battalion, where I have been embedded

with my writer, Jim Landers. Lt. Col. Oehl has announced a talent show

to keep spirits up and the Marines take this opportunity to strut their

stuff: the good, the bad, and indeed, the ugly. It’s a numbing

show, like something out of a movie. It’s not quite real, and

yet the clapping reverberates in my heart and reminds me that the dust

and grit is very real. Each person there knows that with every hearty

laugh and every good-humored joke that we will go to war, and it is

highly likely that some of us will not return.

Before

me is a crowd of some 2000 U.S. Marines. Sweat and dust cover their

tanned faces and have become woven into the threads of their khaki uniforms.

They stand in the cool evening of a Kuwaiti desert in the barracks called

Camp Coyote, home of the Second Tank Battalion, where I have been embedded

with my writer, Jim Landers. Lt. Col. Oehl has announced a talent show

to keep spirits up and the Marines take this opportunity to strut their

stuff: the good, the bad, and indeed, the ugly. It’s a numbing

show, like something out of a movie. It’s not quite real, and

yet the clapping reverberates in my heart and reminds me that the dust

and grit is very real. Each person there knows that with every hearty

laugh and every good-humored joke that we will go to war, and it is

highly likely that some of us will not return. On

the morning that President Bush was scheduled to make his speech declaring

war, we were awakened with a start at 3 am and told to pack: we were

leaving in three hours for war. I made quick decisions in the dark about

what to bring and what to leave in my secondary bag, the one that would

follow in the field train some eight hours behind. We were supposed

to have two days’ notice to prepare, to let loved ones know that

they would not hear from us for awhile...until we entered Iraq. Instead

we woke up to the shock of war: tanks rumbling over the earth beneath

us, and no way for us to call. The goal was to surprise the Iraqis with

our stealth. We proceeded to the DA, short for dispersal area. The Lieutenant

Colonel decided not to move us temporarily to a TAA, a tactical assembly

area, whereupon the troops then move to the DA, and then on to cross

the LA, the line of departure or, in other words, the border.

On

the morning that President Bush was scheduled to make his speech declaring

war, we were awakened with a start at 3 am and told to pack: we were

leaving in three hours for war. I made quick decisions in the dark about

what to bring and what to leave in my secondary bag, the one that would

follow in the field train some eight hours behind. We were supposed

to have two days’ notice to prepare, to let loved ones know that

they would not hear from us for awhile...until we entered Iraq. Instead

we woke up to the shock of war: tanks rumbling over the earth beneath

us, and no way for us to call. The goal was to surprise the Iraqis with

our stealth. We proceeded to the DA, short for dispersal area. The Lieutenant

Colonel decided not to move us temporarily to a TAA, a tactical assembly

area, whereupon the troops then move to the DA, and then on to cross

the LA, the line of departure or, in other words, the border. It’s

been a few days since that momentous night: March 20,2003. We were some

of the first to enter Iraq, but have seen little action as we progress

north. It is not good strategy for a tank battalion to enter smaller

towns where it cannot maneuver the streets and damage sewage lines,

so we work our way west and let the infantry take the towns and cities

of Al Basrah and An Nasiriyah. I am frustrated to not be exposed to

any action and I continue to make pictures of Marines sleeping, convoying,

surviving dust storms and getting ready for battles that never materialize.

I came to cover a war, but it has become so dangerous that my bosses

won’t permit me to cover anything independently. I must continue

traveling with the military.

It’s

been a few days since that momentous night: March 20,2003. We were some

of the first to enter Iraq, but have seen little action as we progress

north. It is not good strategy for a tank battalion to enter smaller

towns where it cannot maneuver the streets and damage sewage lines,

so we work our way west and let the infantry take the towns and cities

of Al Basrah and An Nasiriyah. I am frustrated to not be exposed to

any action and I continue to make pictures of Marines sleeping, convoying,

surviving dust storms and getting ready for battles that never materialize.

I came to cover a war, but it has become so dangerous that my bosses

won’t permit me to cover anything independently. I must continue

traveling with the military. At

this point we are headed north to take on one of the last Iraqi army

divisions in the north. The Marines are not set up to travel more than

60 miles away from port, yet we are some 300 miles away from the nearest

one and our supply trains can hardly keep up with us. We wait for days

for the fuel trucks to arrive, only to have enough fuel to travel 30

miles.

At

this point we are headed north to take on one of the last Iraqi army

divisions in the north. The Marines are not set up to travel more than

60 miles away from port, yet we are some 300 miles away from the nearest

one and our supply trains can hardly keep up with us. We wait for days

for the fuel trucks to arrive, only to have enough fuel to travel 30

miles. I

haven’t had a wash in six days and am as dirty as I can recall

ever being in my entire life. We are living in some of the dirtiest

conditions imaginable with dust; dust and more dust everywhere and still

no bath in sight. We live in extreme heat during the day with wet, chilled

temperatures at night. All my companions are sick with respiratory infections.

I, too, have developed a cold and appease myself from the complete misery

of the situation with little bits of chocolate I bought before leaving

Kuwait. There are no more tents, no more sleeping bags, just body armor

to keep one’s neck propped up at night. There is no comfortable

position. We must be ready to leave at a moment’s notice.

I

haven’t had a wash in six days and am as dirty as I can recall

ever being in my entire life. We are living in some of the dirtiest

conditions imaginable with dust; dust and more dust everywhere and still

no bath in sight. We live in extreme heat during the day with wet, chilled

temperatures at night. All my companions are sick with respiratory infections.

I, too, have developed a cold and appease myself from the complete misery

of the situation with little bits of chocolate I bought before leaving

Kuwait. There are no more tents, no more sleeping bags, just body armor

to keep one’s neck propped up at night. There is no comfortable

position. We must be ready to leave at a moment’s notice. A

couple of nights ago, we arrived at our new camp after traveling some

ungodly amount of miles with the tanks. Exhausted and cranky, I prepared

to fight with my satellite phone to try and transmit some images from

the field. Five minutes later, a 50-caliber machine gun blasted several

rounds just yards from me. A young infantryman grabbed me and threw

me to the ground, covering me with his body. He dragged me up and then

pushed me toward the back of a hummer. Eyes wide and fearful, I breathed

hard and painfully as we waited for another round to fire. It was so

close that our chances for escape would have been low if indeed we were

under attack. Moments later, screams of A positive! filtered through

the dark night and we realized that someone had been hurt. It was a

26-year-old Lance Corporal from New York, and he was dead immediately.

A fellow tanker had accidentally pressed the safety switch on his gun

while getting out of his tank and it set the machine off killing the

lance corporal in the neighboring tank. Although I am permitted by the

rules of our embedment to photograph such situations, the Marines in

charge were too freaked and would not permit me to make photographs.

I can understand their sentiments. But I explained to them that I am

not traveling with them to do a public relations campaign. I am there

to document their experiences, in all that entails. War sometimes entails

death. It’s difficult to imagine what our military personnel go

through to conduct a war. It is truly the most wretched of circumstances.

Even before I met up with the Marines at Camp Coyote, some hadn’t

had a shower in weeks. Many suffer from trenchfoot and other unsavory

conditions. Yet they continue to work as hard as they can to do their

jobs right and with pride. It struck me immediately when I entered the

sphere of the Americans in Kuwait. Whereas in my five-star hotel in

Kuwait I never knew if a man would walk ahead of me or behind me through

a door, I always knew among the Marines that I would be given the right

of first entry. It feels good to be among our men. Chivalry is still

alive among them.

A

couple of nights ago, we arrived at our new camp after traveling some

ungodly amount of miles with the tanks. Exhausted and cranky, I prepared

to fight with my satellite phone to try and transmit some images from

the field. Five minutes later, a 50-caliber machine gun blasted several

rounds just yards from me. A young infantryman grabbed me and threw

me to the ground, covering me with his body. He dragged me up and then

pushed me toward the back of a hummer. Eyes wide and fearful, I breathed

hard and painfully as we waited for another round to fire. It was so

close that our chances for escape would have been low if indeed we were

under attack. Moments later, screams of A positive! filtered through

the dark night and we realized that someone had been hurt. It was a

26-year-old Lance Corporal from New York, and he was dead immediately.

A fellow tanker had accidentally pressed the safety switch on his gun

while getting out of his tank and it set the machine off killing the

lance corporal in the neighboring tank. Although I am permitted by the

rules of our embedment to photograph such situations, the Marines in

charge were too freaked and would not permit me to make photographs.

I can understand their sentiments. But I explained to them that I am

not traveling with them to do a public relations campaign. I am there

to document their experiences, in all that entails. War sometimes entails

death. It’s difficult to imagine what our military personnel go

through to conduct a war. It is truly the most wretched of circumstances.

Even before I met up with the Marines at Camp Coyote, some hadn’t

had a shower in weeks. Many suffer from trenchfoot and other unsavory

conditions. Yet they continue to work as hard as they can to do their

jobs right and with pride. It struck me immediately when I entered the

sphere of the Americans in Kuwait. Whereas in my five-star hotel in

Kuwait I never knew if a man would walk ahead of me or behind me through

a door, I always knew among the Marines that I would be given the right

of first entry. It feels good to be among our men. Chivalry is still

alive among them.