|

→ May 2004 Contents → David Douglas Duncan → Feature

|

David Douglas Duncan

May 2004

|

|

|||

|

It's been 36 years since David Duncan, already long renowned, seemed to step out of Vietnam and into LIFE's New York offices. He had seen more wars and more of life than I ever knew existed. For a young researcher, actually more of a kid, that's when and where the admiration and friendship began. As I retrace all those years in my mind, as I think back over David's long career and the indelible photographs that graced so many pages of LIFE and a small library of books, I have come to a new appreciation: The realization that there is no photographer I hold in greater awe. The power of his work cannot be overshadowed. I find my emotions welling up -- for the years will not erase his genius nor the ability of his photographs to deeply move. Clearly, a time cannot be repeated, but David's enduring legacy of our time will be there for all to witness as the future unfolds. For now, I have many wonderful personal memories and expect to add many more. I think of Mouans-Sartoux last June, of David and the beautiful Sheila at home with Yo-Yo. The influence of David's dear friend Picasso is evident on a magnificent day, one of the very few during that horribly hot summer that took the lives of so many. It is one of those treasured afternoons, enjoying the fine lunch Sheila prepared and sipping on wine as David hurried to meet another deadline: Photo Nomad, his life so far.

********** It was 1968 ... most likely a Tuesday night, the night before we would put the magazine to bed. Late nights were common. Often we pushed our deadlines, if only to better an already closed story. That was LIFE magazine. It's trite, of course, but it is also true: We were a family. We spent more time with each other than with our traditional families, and so much of it was intense, a heady mix of the privilege of working at the pinnacle of photojournalism and a momentous time. Even in casual dress David would have been striking, a former -- no, still, a -- Marine, with movie star looks, tall, with large hazel eyes, and a quiet yet demanding presence. On this night he still wore camouflaged fatigues and combat boots. Gesturing toward the reddish soil, 'The mud of Khe Sanh,' he would answer to the question asked and not asked by all the staffers who found their way to the Picture Department. It was an era when LIFE was present on every front. We had exclusive rights to the space program, and a couple of years before had chartered a specially fitted airliner to lift a large editorial staff to Churchill's State funeral. The photographs were processed and the magazine laid out on the plane as it flew back from London to the printers in Chicago. Khe Sanh was a big story. On this night, as he approached my desk, he looked at me kindly, and softly introduced himself: 'I'm David Douglas Duncan.' There he was, straight from the battlefield. He should have been weary.

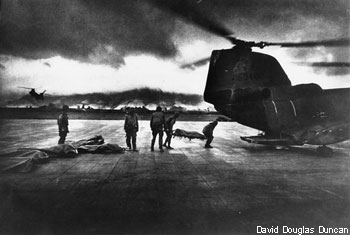

While his Tri-x made its way through the LIFE lab, David adjourned to dinner at Pearl's with a tableful of editors. In the bitter February cold this neighboring Chinese restaurant was a LIFE favorite, made better by the knowledge that a number of its editors were also investors. Tucked up in the northwest corner of South Vietnam, the U.S. Marine outpost at Khe Sanh's proximity to both Laos and the DMZ, supply routes for the enemy's men and materiel, was the very reason for its existence. The military leadership had determined that this was where the enemy had to be stopped. Intelligence estimated that six thousand Marines faced a force of 40,000. Comparisons were made to the situation which had led to the French defeat at Dien Bien Phu fourteen years earlier. For months Khe Sanh dominated the news from Vietnam, later sharing the headlines with the pivotal 1968 Tet offensive. In a still unresolved debate, one side argues that Khe Sanh was just a 'feint' to draw troops away from South Vietnam's urban areas which were the targets of Tet. Whatever the truth, Khe Sanh was important. President Johnson had even had the Pentagon build a table model of the Khe Sanh plateau for the White House basement Situation Room. Through weeks of incoming bombardment, the encircled Marines fought back, while unprecedented American air power pounded the besieging North Vietnamese. Almost 500 Marines were lost, perhaps twenty times as many of the enemy. Inside the camp, along with the explosions, the heroism and the death, Duncan also caught the pain and even a tenderness. The enduring effectiveness of his work is not in some photographic illustration of 'body count,' a concept David so vehemently abhorred, but in the faces and, closer still, in the intensity of a soldiers' eyes. Their stare alone can tell the story of the horrors of war. "I'm one at heart," David said of the Marines. "I know their character from the past. There's something kind of marvelous about them; it's their simplicity, their generosity, their casual sharing of everything they have." The signature photographer of the Korean War was back with his beloved Marines, and the pictures show it: His last frames from Khe Sanh, grainy gravure black and grays of helicopters carrying out the dead.

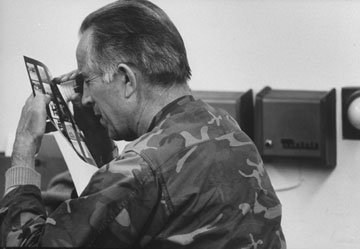

Two black Leica M3D's -- specially modified for him, the significance of the appended 'D' obvious, of course -- accompanied him in his rucksack, the other two were undergoing repair in Hong Kong. All four survive to this day. Less lucky was the snub nosed Colt .38, the 'banker's special' he had long carried, gone from a desk where he laid it at Da Nang that day. Too tempting also were the Nikon-laden Halliburtons, left 'safely' in a corner of the base. He never saw either again. Past the unpleasant MP who demanded of Duncan: 'Your papers?' the silver oak leaf earned him a seat out of Da Nang on a huge C-141 Starlifter, its wings so long that their tips 'almost seemed to scrape the ground.' Through Okinawa to Dover, Delaware, his only company were the dead, probably not yet those from Khe Sanh, making their last trip home. Still almost 200 miles from New York City and, despite the combat gear, clearly a civilian now on U.S. soil, Duncan did the obvious: He hailed a cab. A taxi with a driver naturally reluctant to make such a trip. If you can imagine the charm needed to persuade an Egyptian President to throw open to a single photographer a then sealed off Gaza, or to win from a Soviet Premier an invitation to be the first to photograph the Kremlin's treasures, it is simple to understand how David encouraged the driver to take his wife for a couple of days in Manhattan. Finally, Duncan and his film, the driver and his wife, would be in Rockefeller Center. At speed, in tanker traffic somewhere just outside Trenton a tire blew. It was a sound that at Khe Sanh would have foretold terrible consequences, even near the Pennsylvania border it could was been much worse. Safely to the side of the road, David easily saw the irony. Even now he laughs, sketching his own obituary -- the survivor of so much 'gets clobbered' on the New Jersey Turnpike. From Pearl's, where actor Anthony Quinn had joined them from a nearby table, the LIFE crew returned to its editing duties. As Gjon Milli photographed, David examined his contacts. The prints would be made overnight. Around the 29th floor, the cocktail-stocked credenzas were open for business. As cigarettes burned carelessly on every desk it seemed, I asked David what he would like. 'Milk, please.' This Marine never drank. Liquor would have been so much easier, midtown Manhattan offered few alternatives on a late night in 1968. But milk was to be found some blocks away in the wintery cold, and my reward was to come a few days later. David invited me to indulge in a mutual weakness -- milkshakes at Rumpelmeyers. A delightful afternoon to be cherished and fondly remembered by both of us. By the weekend, eight million magazines were on their way to subscribers. Splashed across the February 23 cover above skater Peggy Fleming draped in Olympic gold: 'Khe Sanh, Photographed by David Douglas Duncan.' Inside, 12 black and white pages brought gritty reality to the countless words already written about bombing tonnage and body counts. Nary a word told of David Douglas Duncan's ordeal nor the day-old mud on his boots. A few weeks later he would publish 250,000 copies of a $1 book, its proceeds to benefit the families of those killed at Khe Sanh: I Protest. But now it was after midnight New York time, and half the world away from where his day had started -- in other ways, so much farther still -- Duncan approached the Plaza's reception desk. 'Excuse me, sir,' questioned the young man escorting his girlfriend through the hotel's lobby and clearly believing that this was the home away from home for many a movie star. 'Have you just come from a shooting location?' 'Yes' was Duncan's one word reply.

© Barbara Baker Burrows

|

||||

Back to May 2004 Contents |

|

'Messengers come now to carry off the fallen men of that day's battle.

Men joining those other men killed in all other wars. Then they were

gone. And it was night.' [D.D.D., War Without Heroes.]

So too began Duncan's journey. Jumping a helicopter to the Rockpile

with Khe Sanh's senior commander, Major General Rathvon Tompkins, he

continued on to Da Nang. Again he was among friends, comrades from

previous wars. A borrowed silver oak leaf, the insignia of a lieutenant

colonel, a rank to which he was properly entitled as a Marine reservist,

was to be his passport.

'Messengers come now to carry off the fallen men of that day's battle.

Men joining those other men killed in all other wars. Then they were

gone. And it was night.' [D.D.D., War Without Heroes.]

So too began Duncan's journey. Jumping a helicopter to the Rockpile

with Khe Sanh's senior commander, Major General Rathvon Tompkins, he

continued on to Da Nang. Again he was among friends, comrades from

previous wars. A borrowed silver oak leaf, the insignia of a lieutenant

colonel, a rank to which he was properly entitled as a Marine reservist,

was to be his passport.