|

→ June 2006 Contents → Column

|

American Idyll

June 2006 |

|

||||||||||||

|

We live in an age of bumper-sticker patriotism in the United States, full of empty declarations like "The Power of Pride" and "United We Stand." We slap them on the back of our cars or wear them on our tee shirts, and they give us comfortable, feel-good satisfaction, and a sense that we belong. In the end, however, they don't help us understand our country, or appreciate it. They are simple, emotional shortcuts that marginally relate to one aspect of this complex and intriguing land.

His way of looking at his world and the way that he captures it was influenced in no small part by Henri Cartier-Bresson, who advised him early in his career to look at the work of the Quattrocentro painters. What an investigation of their efforts taught him was to compose not just from left to right, but from back to front, working the picture in multiple planes, and often narrating several smaller stories within the overall image. It is a feat that he finds easier to achieve through the optical viewfinder of a Leica, or the larger formats of the Hasselblad and view camera, the latter being the equipment that he favors in his present work.

He is fond of quoting Charles Harbutt's saying, "I try to let the pictures take me rather than me take the pictures." It's probably more accurate to substitute the word "find" for the word "take" because Uzzle goes to great lengths to take the picture once it finds him. He roams the back roads, never flying whenever he can drive to a destination, and often factoring in, at his own expense, several days to arrive at a location for the few annual reports that he will undertake each year in order to sustain his wandering ways. The strange and wonderful sights that he finds are usually not available to those who ply the interstate, but on the road less traveled "the stuff just kind of pops up at me." He relies on his intuition when he arrives somewhere. "There's a feeling I will have or not have about a place. I'll come into a small town, and if it seems interesting and it's a nice time of day, and the light's nice then I'll just start driving up and down the side roads. It might take me an hour and a half to get to the other side of a small town because I'll go down every little street. I find an awful lot of stuff by just being stubbornly thorough in what I'm looking at."

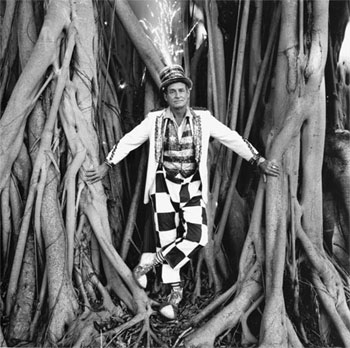

Once the picture has found him he will go through the elaborate process of capturing it on film. If this involves people, and many of his photographs don't, he will solicit their cooperation. He has found that the longer he takes to set up the picture, and the more elaborate that set up is, the more ready his subjects are to collaborate with him. This is yet another reason to work on the larger-format cameras mounted on a tripod, often on the roof of his van. They seem to realize that the trouble that he takes is an indication of how seriously he takes his calling. Although he is serious about his photographs, most of them are infused with a wonderfully gentle and affectionate humor that is in no way sardonic. Here too there is collaboration, as if the subjects are saying, "Okay, this may be silly, but it's part of me, and without it I would be someone else." The chairs on the porch of a simple house are full of stuffed toys being watched through the window by the couple that has put them there; a woman showing the androgyny of old age poses her head in the top of a Superman cutout, her spectacles a reflection of those on the Clark Kent silhouette behind her.

Humor is incredibly hard to convey in photography, as anyone who has had to judge that category in a photo contest will confirm, and Uzzle is one of the very few who do it successfully. He attributes this to his habit of looking in what he terms the wrong places. "I'll look at something and what's behind it, or round to the side of it rather than just lining things up in a logical fashion. I'll step to the other side; it comes very naturally for me to do that. I don't really think it out at the time I'm doing it." He goes on to say, "You can't force humor; the minute it starts happening like that it becomes a corny, poor, crude joke. Jokes are really crude in photography so you just have to kind of let things happen in a very sly way. Elliot [Erwitt] is so good at being very cagey with humor." Much of what works about the humor in Uzzle's photographs depends not on what the pictures tell you but what they keep to themselves. What on earth are those grandiose columns doing in front of a doublewide, not to mention the blank grave markers? And just why is there an anti-aircraft gun at the end of a row of mailboxes? The answers to these puzzles lie in our imagination and are therefore probably much more amusing than the mundane real-life explanations.

He didn't know what to call the book until his editor and publisher, Garrett White, suggested that they use the title of one of the pictures. The photograph shows the lower halves of a man and woman, each of whom is holding a greyhound. All four are wearing clothing in the pattern of a Dalmatian's spots, weird enough for human beings, but doubly so for greyhounds. Imagine Uzzle's delight when as he says, "You know those people and their dogs came to the opening of the show at the Southeast Museum of Photography. They came in their polka dots, in their same tee shirts and they were just great, and they walked around with their dogs and it was wonderful."

In a time when it has often been a challenge to be a proud American it is refreshing to have a photographer who can remind you that there are any number of people down the back roads and byways of this vast and complex land who are indeed wonderful.

[Burk Uzzle's book, "A Family Named Spot," can be ordered online at www.Amazon.com or Barnes & Noble, www.BN.com. The book, and others by Five Ties Publishing , are distributed to the trade through Consortium Book Sales and Distribution: www.cbsd.com. Toll-free number: 800-283-3572.]

© Peter Howe

Executive Editor

|

|||||||||||||

Back to June 2006 Contents

|

|