|

→ December 2007 Contents → E-Bits

|

E-Bits:

The Decisive Moment May Be A Blur December 2007

|

|

|

There is one subject that keeps coming up in the digital age, and it is related to McLuhan's notion that the medium is the message. Well, it is. So what is the message of the digital age? It seems to be an age where anything is possible, and that includes in the field of photography. Depending on the instrument, the vision is vastly different, and there is a lot to choose from now, even for those of us who went dormant as film cameras began to give way to the digital world.

Henri Cartier-Bresson gave us "The Decisive Moment," and in so naming that moment he defined the goal of photography perhaps for all time, reaching far behind him as well as into an unknowable future. He was an artist who painted too, but for Cartier-Bresson the photographer, that moment was, in his words, "the simultaneous recognition, in a fraction of a second, of the significance of an event as well as of a precise organization of forms that give that event its proper expression." When Cartier-Bresson offered his definition, he may not have realized that he also created a philosophy so broad as to be universal, and it would go viral in his world and the next. By the "next," I am talking about cyberspace. In the digital universe wherein photography is but one medium among many, that may translate to whatever achieves instant communication, be it the still photo, audio soundtrack, video, graphic illustration, cartoon, animation, written or verbal storytelling.

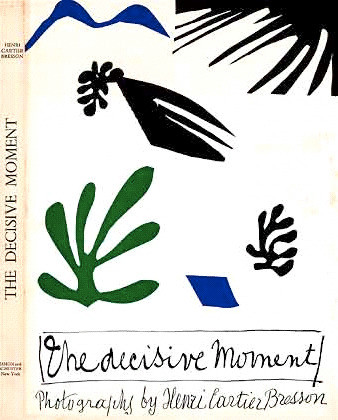

Cartier-Bresson's 1952 book of the same name is rare indeed and many a library does not even have a copy. However, with miracles at our fingertips, we can find a reproduction on the Internet. All of us can view the book online at any time, night or day, on any day of our choosing. Click on the cover image to go to "e-photobooks dot com" to see a good clean copy of "The Decisive Moment," which contains not only Cartier-Bresson's thought-provoking philosophy but also a portfolio of his most stunning and memorable work.

"Il n'y a rien dans ce monde qui n'ait un moment decisif"

So what is the decisive moment really all about, and what do we think about it in 2007? Like many who fell in love with still photography and took up its quest through photojournalism, I was initially inspired by the work of Cartier-Bresson, the unchallenged father of photojournalism. Anyone looking to express "reality" and who was trying to communicate authenticity found gospel in the idea of candid, unmanipulated shots. Some were hard-liners – I was – and insisted on available light and uncropped images as well. Some of us turned into a nearly extinct breed when digital cameras first became popularized in the '80s. Until then, I had one camera and one camera only: a manual Nikkormat FT2, and would not consider using anything else. It had a unwaveringly accurate internal light meter and I loved the way the little needle would drift up and down with great sensitivity, appealing to my intuitive decision of how much to open up or shut down the aperture. I remember only one frustration, that the Nikkormat's image finding eyepiece was only 97% true, because 3% could make an enormous difference in positioning and composition. I eventually learned to compensate for the error, but could never figure out why in such an exotic machine like my fine camera the coordination between the viewfinder and the resulting image could not be 100% exact. Perhaps, and probably, the Leica was better, but it was prohibitively expensive and besides, I had started with Nikkormat and intended to stay in the marriage. In those days, we used to talk about the camera being an extension of your arm, like another appendage, or that we were wedded to it. It was, and I was. Read more about it by clicking on the image.

But along came automated cameras, and print technology was changing as well. Suddenly, bafflingly, I couldn't even take the kinds of photos I wanted with my own camera. The technology literally changed my vision and I had a new set of parameters from my employers. My own failing, perhaps, but what the magazines wanted were the latest in crystal clear, sharp images that were more on the order of set-up studio shots with posed subjects rather than candid images bathed in available light where one captured rather than created an image. I hated it. The new demands spawned by changing technology put a kink in the works of my neural system it seemed. Photographically speaking, it was a tumultuous time. I bought a Nikon F3 (shudder) to continue eking out a living in photography. The market demanded it. I always returned to my Nikkormat, however, the camera that was my true love. I refused to do anything but black-and-white (a self-imposed death sentence), and when several magazines where I freelanced finally died of their own external pressures, so, nearly, did I. Here was my photographic executioner:

With ambitions and even basic equipment threatened, I found myself on the path of many who didn't want to make the initial leap from manual camera, black-and-white film photography to the digital world of color, snap and technological panache, Events drove me the other way, into drawing and art, still trying to capture something real in my own way. I had already begun keeping an illustrated diary, and so got serious about it, and still do it even to this day. I have just started my 183rd volume, and I need more closet space to accommodate what now amounts to over 12 linear feet of diaries. I could never get photojournalism completely out of my system though I thought it best to try. I did a book in the mid-'90s with black-and-white photos using my same trusty Nikkormat. I went on to do research in academics, thinking I was giving up photography forever, but when I wrote papers and put tons of images with the text, going to the library in search of them became the same thing to me as a photo assignment without jet lag or darkroom time. I learned that we adapt, and the energy we have expresses itself in new ways

Somewhere along the way I still needed to document everything, so when I discovered disposable black-and-white film cameras at some drugstore, I found a new toy and a new friend. I couldn't do photography with them, exactly, and there were no real decisive moments I could capture with any gratification, but using these throwaways could produce a record. Cheap, recyclable, lightweight, decidedly anti-digital and unobtrusive, these cameras could go with me everywhere, so I hunted for discounts and bought them 40-at-a-time. The worst things about them were that the flash was compulsory and the viewfinder was so inaccurate as to be horrifying - not off by 3% but more like 50%. They were smaller but not even as accurate as a Brownie had been. It was impossible to photograph what I saw, and with no decisive moments, the photographic heart stops beating. Zombie photography it was, maybe, but it was fun in another way. It was totally unprofessional, off the record and experimental, and though I hated the flash and bizarre non-resonance of the images, I discovered my friends and strangers alike enjoyed having duplicates of images (a drugstore bonanza) captured by my wayward and errant, somewhat cheesy little camera. Cartier-Bresson it was not, in fact one could fairly well say it was HCB at apogee (as far away as you can get), but what the heck, it was a private record not for show. My decisive moments had begun to be elsewhere in a non-visual realm. I couldn't hope to capture moments of the unseen on film and didn't try, although every now and then something nice would appear. By surprise. I must pause to show you something that no low-tech camera could ever hope to capture. An e-mail arrived last week containing a gallery of photos labeled, "Between the Seconds." We do not know the identity of the photographers, whose beautiful work is zipping around through cyberspace. See it here:

Joseph Campbell once said something like, "what is life but loss, loss, loss?" True enough in all things, and sure enough, Kodak began to phase out precisely the little black-and-white film camera I had incorporated into my daily M.O. I'd grown used to having a pocket camera, and was forced by this turn of events to buy a little digital one to continue what has become an addiction---snapping photos of whomever or whatever, wherever I am. Here comes the "blur" reference that is mentioned in the title.

Dang technology. I bought a Nikon Coolpix S50, a nice, small digital with a huge screen that can be set to black-and-white. I never use the flash because for the most part it has an amazing ability to gather light, and I can still be relatively unobtrusive though it does beam an annoying infra-red light on the subject when it focuses. I can control the relative aperture setting to under- or over-expose as I wish, and it can go macro. It is an interesting device. I love it, sort of, and it's almost making me begin to think visually again. Somehow, though, it still doesn't feel like real photography to me. Almost, but not quite. And the reason is the delay between pressing the shutter release and its opening. Whatever moment I saw is long gone by that time, and this technology totally misses it. Though the visual field is an improvement, nearly 100% accurate, the shutter speed is slower than molasses especially because I use available light only. So ridiculously slow, slow, slow is it, the result is often one big blur, like these that I shot recently.

So now I'm coming to the point of this whole article. No one could argue the profundity of seeing a mass of water still undispersed as it drops, or in any of the other time-stopping photos in "Between the Seconds." They are simply incredible. The split-second images show details contained in reality that normally go unseen but are revealed exquisitely by the technological eye of a lightning-fast, sophisticated state of the art digital camera. But what about the other way around, where time is slowed down, where one moment melts into the next, yielding not a sharp focus of the world but a soft one where nothing stands still? What do we want but to see things as they really are, but on what terms? Do we want a microsecond snapshot or a long, contemplative view? When I got my little pocket camera, I disliked the fuzzy photos so often full of movement. There is rarely a sharp photo among them. "Dirty" photos they are called. Occasionally - and this is never trying to - this slow shutter speed with almost impossibly good night vision produces something that is interesting, even if it is not calculated. I've come to see value there as well, and find there is mystery and inspiration on both ends of the continuum. Said another way, it is interesting to see what you get when you don't get what you want. Sometimes, a decisive moment may be a blur. Isn't life like that? And it makes one think about reality in a whole new way.

© Beverly Spicer

The links that appear in this column are from World Wide Web. Credit is given where the creator is known, or the image is linked to the site where it was found. The Digital Journalist and the author claim no copyright ownership of any video or photographic materials that appear herein. |

|

Back to December 2007 Contents

|

|