Way back in 1999, I wrote an editorial lamenting how difficult it was becoming to pursue a life in photojournalism. Budgets were being slashed at the newsmagazines for photography, entry-level jobs at newspapers were becoming increasingly difficult to obtain, and once such an internship was secured, it was hard to move up the ladder. Compared to the glory days of photojournalism in the 1970s, the situation was looking bleak.

As I reread that article recently, I realized that what I was talking about then were some cracks in the dam. Today, the whole damned dam is gone. It is difficult not to be concerned by the changes in the industry over the past year. Newsmagazines are not exempt from these changes. Time and Newsweek once had an extremely heated and competitive battle each week to get the very best photographers on the big stories of the week. During the 1982 siege of Beirut, I headed a "delta team" for Time magazine of no less than 10 photographers covering that struggle day in and day out for more than a month. On a major presidential international trip, there would be at least three or four contract photographers flying with the president, with stringers picked up along the way. Radio repeaters were set up to coordinate the photographers' movements. Advance trips were made by the photographers to chart the story.

The newsmagazines were once the market of choice for photographers and agencies. Together Time and Newsweek provided the best places to work. Today, as any photo agency head will tell you, they simply no longer provide the financial support that once kept the business going.

In hopes of saving the brand, Newsweek recently did a complete makeover. The magazine could no longer compete with the Internet, with decreased readership and lost advertising. The first thing to go was the news.

In hopes of saving the brand, Newsweek recently did a complete makeover. The magazine could no longer compete with the Internet, with decreased readership and lost advertising. The first thing to go was the news.

According to its editor, Jon Meacham, the intent was to turn Newsweek into a watered down version of The Economist. The magazine is now too soft. It is no longer about news. It does not work.

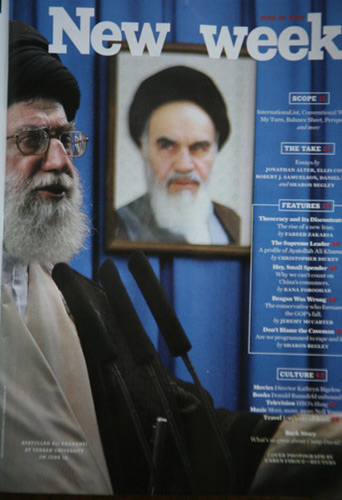

An editor of The Wall Street Journal said a long time ago, "The great benefit of not using pictures was you don't need photographers." That is becoming truer all the time. For the most part pictures are certainly gone from the new layout at Newsweek. Although the June 20th issue featured several spreads of pictures from the protests in Iran to accompany a Fareed Zakaria article, compared to Time's coverage they seemed to be afterthoughts.

Over at Time, things are not really better. Pleas by their contract photographers to be sent to Iran in advance of the 30th anniversary of the revolution were rebuffed.

One of Time's top contract photographers reported that last year he only had three assignments, and that was in an election year.

Meanwhile, things are even worse at newspapers. Back when the newsmagazines were sending flocks of photographers flying around the globe, the newspapers, funded by more than 20% profit ratios, were investing heavily in their photo departments. Papers like The New York Times, The Washington Post, the Chicago Tribune; and The Dallas Morning News were all vying for the best photojournalists they could find and then they sent them off on long-term projects, which won countless Pulitzer Prizes.

Of course, like all good things, this culture has been torn apart as these papers now struggle to survive. We all know about papers like the fabled Rocky Mountain News and Seattle Post-Intelligencer, which have folded this year. The Chicago Tribune Company is in bankruptcy. Hundreds of photojournalists have been thrown out of what they considered "jobs for life."

In 1999, video journalism was only a ray of light on the horizon. Ten years later, despite the training programs by such organizations as The Platypus Workshop and the National Press Photographers workshops, newspapers that were leading the march into multimedia, such as the Detroit Free Press, are pulling back on those initiatives as they struggle to survive. The FREEP no longer even makes home deliveries of their paper to the readers.

And the situation is even grimmer in television. Newsroom budgets are being slashed at networks and affiliates. Photojournalists who had won prizes for their stations are now pounding the street, but minus those betacams.

Meanwhile, what we looked forward to in 1999, the emergence of the World Wide Web as a principal news provider, has happened beyond our wildest expectations. The problem is that the revenue in advertising has not kept up with the Web's growth. Although a newspaper Web site's unique views can dwarf the print edition's circulation, the revenue derived from Web advertising is often less than 10 percent of print ads. Yet, it is this weak stream of revenue that publishers are turning to just to keep their print editions in existence.

What this means is that revenue available to pay visual journalists just isn't there.

However, publishers realize that they must get those advertising dollars up. There are constant industry meetings as they try to come up with standardization of online ad rates. But as they sort this out, which eventually they will, many print editions will disappear and major brands will cease publication both in print and on the Web.

So, change has come. We are in what I am afraid are only the opening moments of an economic adjustment that will affect everyone. Steve Balmer, the CEO of Microsoft, recently told an audience in Cannes, "I don't think we are in a recession; I think we have reset," he said. "A recession implies recovery [to pre-recession levels] and for planning purposes I don't think we will. We have reset and won't rebound and re-grow."

In the meantime, papers like "the old grey lady," The New York Times, are hanging in there. They still have the best photo department in the world, in my estimation, and the quality of pictures and video just keeps getting better. Amidst all of the chatter on Twitter and YouTube during the protests in Iran, there was a lone professional voice reporting from the streets, and that was the Times' Roger Cohen. With all other Western media barred from covering the protests, Cohen provided a reliable window into a complex and dangerous story. His reports were a testimony of the value of papers like the Times. They paid for him to be there. Without people like Cohen, the world would be a sorry place.

At the end of the day, whether Time or The New York Times survives is irrelevant. The real question is, who is going to PAY professional journalists such as Cohen to go to these news scenes? Professionals do matter. If you broke your leg and your choice would be to have your neighbor who had faithfully watched every episode of "ER" set it, or go to a hospital, there is no question what you would do.

In a recent Platypus class, my students asked me, "Why would you be a photojournalist today?" I answered, "You have to be crazy." I have always considered being crazy as important to a photographer as being curious. Constitutionally, we thrive on chaos and challenge. Being a photojournalist is more a calling than a trade. Those people who will do anything to come back with a story will be out there shooting for a long time.

Dirck Halstead was Time magazine's Senior White House Photographer for 29 years. He now is the Publisher and Editor of The Digital Journalist, the monthly online magazine for visual journalism, and a Senior Fellow at the Center For American History at the University of Texas in Austin. His new book, MOMENTS IN TIME, published by Harry N. Abrams, is in bookstores, and available from Amazon.com.