When we got the word during the last administration that reality would be turned on its ear, nobody had a clue that the traditional venue of newspapers and magazines would be threatened right out of existence. Whether that will happen in toto is yet to be determined, but the new reality is clear: the entire industry is fighting for its life.

Despite hopes of a philanthropic bailout for the major papers expressed in Dirck Halstead's editorial of last month, and suggestion of euthanasia or suicide of ailing newspapers in this month's provocative essay by Common Cents editor Mark Loundy, it's not clear that either one of those things is going to happen. What philanthropic organization is going to spring for a major newspaper that it can't control, and what newspaper is going to terminate itself one moment before it has to?

Most newspapers have moved online while shrinking their dailies to smaller dimensions and less pages, but none have completely given up the ghost, stopped the presses, or quit distributing a physical paper unless forced to. Those that have died already were simply driven to their deaths through economic starvation.

Many of us never dreamt that the printed newspaper and its brand of journalism might be finite, having a physical life cycle that began shortly after the printing press was invented, and terminating early in the 21st century—virtual reality notwithstanding. Who in the beginning could have foreseen the digital age in cyberspace and what it would mean for the news?

Citizen journalism? The printing press made scribes obsolete and gave birth to authors publishing opinions in books, but the journalist was created by the newspaper. Professional journalism was the work of printers, claims the Knight Citizen News Network. Once journalism was established as a profession, the very phrase "citizen journalism" was an unknown concept that would have been ridiculed when newspapers dominated in the middle of their life cycle.

During the print-dominant era that clearly is passing, for an ordinary citizen to find a venue to publish an independent take on a news event would have been about as laughable as in 1963, for instance, when TV character Gomer Pyle screamed "Citizen's Arrest! Citizen's Arrest!"—a cry broadcast to an entire generation of viewers that now lives in many a TV-programmed memory. In the digital age, citizen journalism—a once outdated concept with a new name—has been reborn.

What does this rebirth mean? Everyone is an author. Everyone is a journalist. Journalism is dead. Long live journalism!

The government of Venice published the first monthly "newspaper," Notizie Scritte, in 1556. Another of the first printed newspapers was the Oxford Gazette, published on Nov. 16, 1655, in Oxford, England. What will be the last of the print newspapers to survive? For a fascinating look through four centuries of historic newspapers beginning with the Oxford Gazette, watch this short video from the Mitchell Archives.

"How to Run a Newspaper" is a memorable scene from the film "Citizen Kane," Orson Welles' 1941 roman à clef criticizing William Randolph Hearst and the rise of his newspaper empire. The character Kane smugly thought he could keep going 60 years (that seemed like forever), spending a million dollars a year. It's been about that long since the film was made, and Welles' prescient vision of the evolution of newspaper giants was pretty much on target. According to the wordsmith who wrote a Wikipedia comment on the film, the tragic Kane's career in the publishing world is "born of social service, but gradually evolves into a ruthless pursuit of power."

In cinema, documentarian Michael Moore's "Capitalism: A Love Story," is being heavily promoted on the airwaves upon its release to theaters nationwide on Oct. 2. In a Sept. 17 interview in a public affairs forum at The Commonwealth Club, Moore gave his thoughts on the death of newspapers. Greed, he says, killed the newspapers. Moore's insightful one-hour interview can be found on FORA.tv, but here is a short YouTube clip of the segment concerning the death throes of newspapers.

Thirty years ago, nothing seemed more secure than print journalism, democracy, and the concept of 'progress' firmly embedded in the idea of capitalism. At this date, nothing seems more insecure. Think tanks everywhere are trying to solve the problem of the demise of newspapers and the transition of newspaper journalism onto the Web without the entire field of professional—and economically viable—journalism being snuffed out. There are many passionate souls out there who will gather information and publish it online, but will the formal institutions survive? And will professionalism survive? And what of the years of experience threatened to disappear along with jobs in this Mass Extinction of the Newspaper species of journalists?

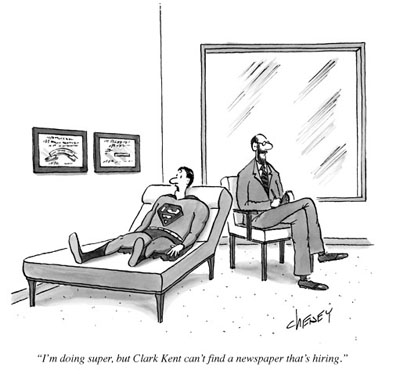

The New Yorker offered the following cartoon by Tom Cheney in the Oct. 5 issue that sums it up. Worth reading in the same publication are Notes by Steve Coll on "Public Media" and "The Future of Journalism," which can be found by clicking on the cartoon.

For anyone still exploring the links in this column, I refer you to an animation about the future of newspapers that has run twice before in E-Bits. Perhaps the third time is the charm. It is called EPIC 2015, by Robin Slone and Matt Thompson for the Museum of Media History. We present it again here:

As the narration begins EPIC 2015, and Dickens so sweepingly said of another revolution, "It is the best of times. It is the worst of times."

Beverly Spicer is a writer, photojournalist, and cartoonist, who faithfully chronicled The International Photo Congresses in Rockport, Maine, from 1987 to 1991. Her book, THE KA'BAH: RHYTHMS OF CULTURE, FAITH AND PHYSIOLOGY, was published in 2003 by University Press of America. She lives in Austin.